By Gift Briton

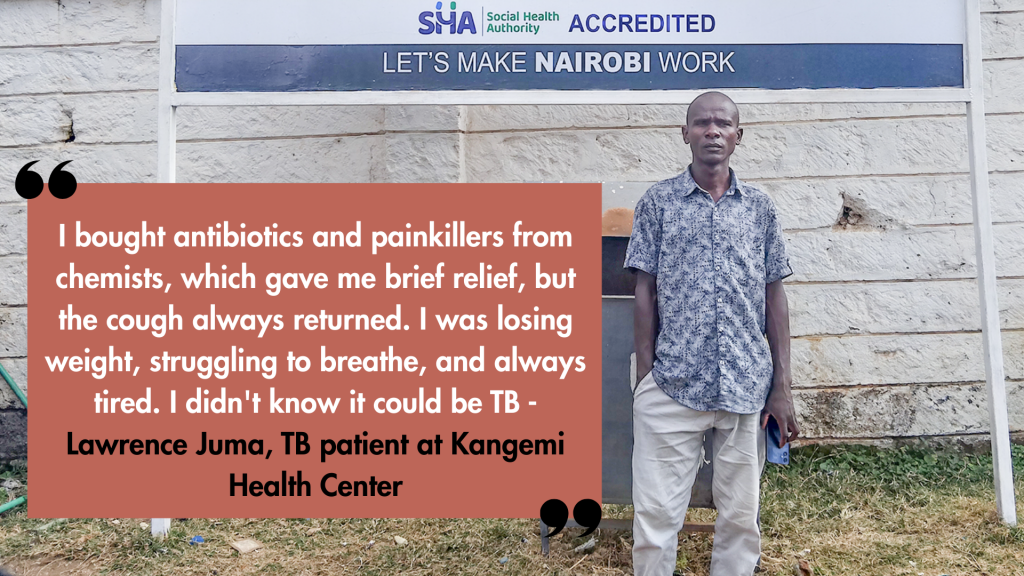

Lawrence Juma walked into Kangemi Health Center in Nairobi not to see a doctor, but to register for the government’s health insurance (Social Health Insurance Fund), which would allow him to take on a tiling contract with a Chinese construction company.

But as he stood in that registration line in June 2025, the 40-year-old tiler had withered to just 92 pounds (about 42 kilograms), with his clothes hanging loosely on his frail body that wheezed with each laboured breath.

For two months, Juma had numbed his painful coughs with over-the-counter antibiotics, telling himself it was just a cold that had settled deep in his chest. He didn’t know he was dying. More dangerously, Juma didn’t think he was killing others.

“I bought antibiotics and painkillers from chemists, which gave me brief relief, but the cough always returned. I was losing weight, struggling to breathe, and always tired. I didn’t know it could be TB,” he said.

The missing 40%

Juma was part of a dangerous national pattern. Nearly 40 percent of TB cases in Kenya go undiagnosed. These missing patients continue to spread the disease unknowingly, fuelling over 15,000 deaths each year.

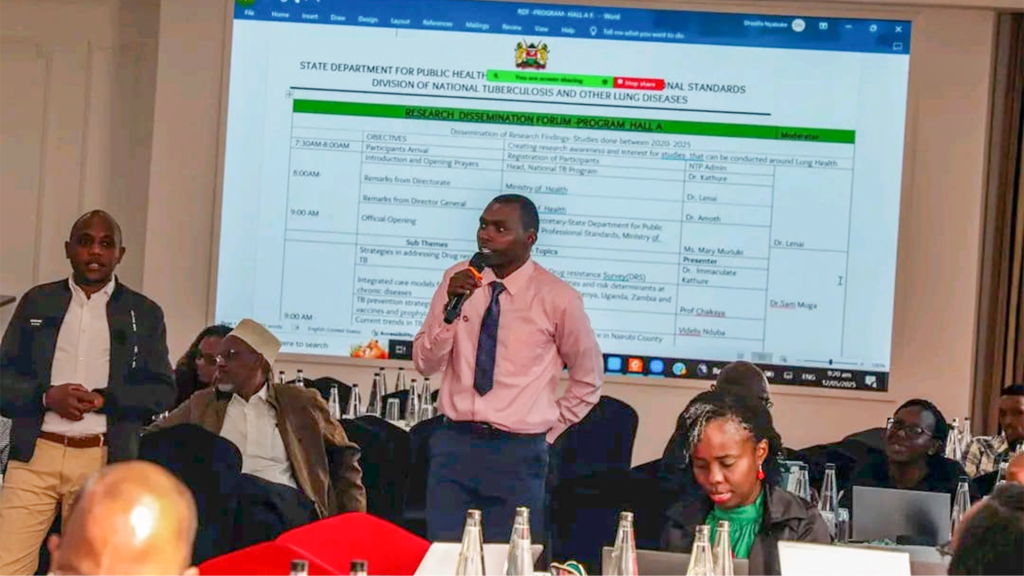

“The biggest gap we have in Kenya in the fight against TB is the people who are infected with TB but have not been diagnosed. The danger is, they’re likely to die of a disease that can be cured, and they’re infecting others too,” said Aiban Rono, Monitoring and Evaluation Officer at the National TB Program, during the March 2025 World TB Day celebration in Nairobi.

Kenya is among the 30 countries carrying 80 percent of the global TB burden. Each year, about 124,000 Kenyans fall sick, with Nairobi County bearing the highest share. Juma was almost one of the unseen casualties of this crisis.

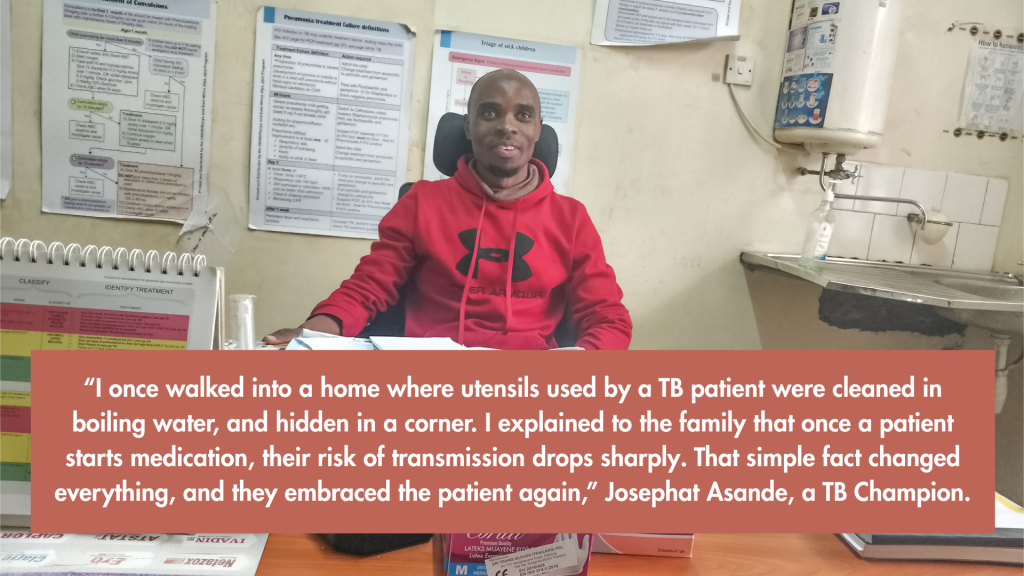

That day, chance placed in Juma’s path a man who had once walked the same road. Josephat Asande, a TB survivor turned volunteer champion, was at Kangemi Health Center that morning. He spotted Juma’s relentless cough and hunched posture in the registration line. In 2015, Asande had survived TB himself, finishing six months of treatment.

“I approached Juma and asked if we could talk in private,” Asande recalled. “I explained the symptoms and urged him to test for TB. He agreed. The next day, his results came back positive.”

For Juma, that moment was the turning point. Further tests revealed the disease had severely scarred his lungs. Doctors told him that any further delay might have been fatal. “If Asande didn’t pick me out of that line, I’d be in a grave today,” Juma reflected.

But Asande became more than the person who found Juma’s TB. He has been Juma’s guide since he was put on medication two months ago. He calls regularly to remind him to take his medication.

He even linked Juma to the Pamoja TB Group, a community-based organization (CBO) that supports patients with undernourishment. Because the hospital had run out of government-supplied Ready-to-Use Foods (RUFs), Juma, whose body mass index (BMI) had fallen below the 18.5 threshold, was selected as a beneficiary. Each month, he now receives a food basket worth approximately 5,000 Kenyan shillings, containing staples such as cooking flour, sugar, beans, green grams, lentils, and milk.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that all TB patients undergo nutritional assessment and counselling at diagnosis and throughout treatment, with access to nutrient-dense foods such as cereals, legumes, dairy products, fruits, and protein sources. Patients typically remain on nutrition support until their BMI improves and stabilises during the six-month treatment course.

Following protocol, Asande did not stop at Juma. With support from the Health Center, Asande and other health workers traced Juma’s closest contacts. Household members were visited directly, tested, and those who were negative were started on preventive therapy. Others, such as Juma’s workmates and friends, were traced through phone calls, encouraging them to report to the nearest health facility for testing.

The Network of Survivors

Asande’s support for Juma reflects a much larger movement. He is one of more than 700 members of the Network of TB Champions, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) registered in 2021. The network is primarily composed of TB survivors who volunteer in their local communities.

Each champion works mainly in the community where they live. They collaborate closely with nearby health facilities, where doctors and nurses supervise their activities. Champions screen people for TB, educate households about prevention and stigma, and support patients throughout treatment, ensuring no one falls through the cracks.

“We are survivors ourselves,” said Stephen Anguva, National Coordinator of the Network of TB Champions in Kenya. “When we tell someone, ‘I was where you are,’ they listen. That is what moves people to screen, to treat, to finish the medication.”

TB spreads through the air when someone coughs or sneezes. Its symptoms, including cough, chest pain, night sweats, weight loss, and fatigue, are easily overlooked. That is why Champions look for more than symptoms. They look for people who might be ignored or hiding.

“Champions work mainly in the villages and neighbourhoods where they live all over Kenya,” Anguva explained. “They don’t wait for patients to come to the hospital; they knock on doors, corner coughing passengers in matatus, and turn every space into a potential lifeline. Typically, each Champion operates within their own sub-county,” Anguva explained.

Champions also have a voice beyond the community. Some serve in national TB technical working groups, where they help shape policies and programmes. Their voice ensures that the realities of survivors inform the country’s strategy.

“It’s passion-driven. Many of us suffered stigma, discrimination, and isolation. We don’t want others to go through the same,” Anguva added.

Becoming a TB Champion is both structured and personal. To qualify, one must have first-hand experience with the disease, either as a survivor or caregiver, and a strong passion for raising awareness. This ensures champions truly understand the challenges TB brings. In each of Kenya’s 47 counties, there is a County Chapter Lead for TB Champions who identifies and recruits potential champions during community forums.

Candidates then complete Tuberculosis 101, a self-paced online course developed by the National TB Program (NTP), which typically takes two days to complete, although some individuals may require more time. After passing, they are added to the county registry, which is linked to the national database of the TB champions.

Found with no symptoms

If Juma represents the danger of late diagnosis, Carol Mwangi shows the invisible face of TB.

In 2024, Mwangi was visiting her cousin in Westlands when a group of TB champions came knocking on doors, urging residents to test for TB and take preventive therapy. One of them was Camila Mwenda, a Champion at Westlands Hospital.

At that time, Mwangi felt fine, with no cough, no night sweats, and no warning signs. But Mwenda persisted. Her gentle insistence convinced Mwangi to take a simple test, which revealed she had latent TB, a hidden infection that could silently progress to active TB. Without Mwenda’s encouragement, Mwangi might never have known, and her condition could have worsened over time.

“My cousin was about to turn them away,” Mwangi said. “She said no one here has those symptoms. But Mwenda was very vocal. She insisted we test. She even said there are drugs you can take to prevent TB if you don’t have it. That made me curious.”

Mwangi agreed to take the test. A day later, the test came back positive. She was shocked.

“I doubted the results. I thought maybe it was a mistake and even went to a different facility to confirm if the result was true,” she said. “It was true. I needed to start treatment. If Mwenda and the group hadn’t come, maybe something worse could have happened.”

Mwenda remembers that day clearly. “Mwangi had latent TB. The bacteria were in her body but not showing,” she said. “That’s why door-to-door work matters. Many people don’t know they carry TB until it’s too late.”

A Mother’s Care

Mwangi credits Mwenda’s persistence and warmth with getting her through treatment.

“Normally, a TB patient is given drugs for a week, then comes back for a refill,” Mwangi recalled. “But one time, the hospital ran out of stock. Instead of giving a few patients a week’s supply, the hospital shared the available drugs among all of us for just two days while waiting for new stock to arrive. Still, Mwenda made sure I never missed a dose. She would even come to the hospital as early as seven in the morning to give me my medication before I went to work. To me, she was like a mother.”

Mwenda sees it as a calling. “Some people think only those with HIV get TB. That stigma makes patients hide,” she said.

From the Margins

Joyce Adhiambo, another Champion, shows how far Champions will go to save lives. A TB survivor and HIV-positive for 24 years, she uses her story to encourage others.

“There was a young man, about 30, who had run away from home and was living in the Dandora dumpsite,” she said. “He refused to take TB drugs. His sister came to me desperate.”

Adhiambo tracked him down. “I told him my story. I said, ‘Look at me, I am living proof you can survive.’ I took him to the facility myself. I did weekly follow-ups until he was healed.”

However, champions like Adhiambo work with limited resources. “Sometimes you want to make consistent follow-ups, but you don’t have transport,” she said. “Sometimes patients deny. They give you the wrong contacts. But you keep going because you know what is at stake.”

These interventions occur thousands of times across Kenya, as champions devise solutions to problems that run deep within the communities. But measuring their exact impact remains a challenge.

“There is no formal system yet to quantify their contribution, though the Ministry of Health is working on a reporting tool that will capture efforts of all players, including Champions,” Anguva noted. For now, their value is measured in stories like Juma’s and Mwangi’s.

Anguva added: “While some counties have embraced Champions, others still don’t recognize them. They are excluded from crucial dialogues about TB. That leaves a big gap, because the voices of survivors are missing where they matter most.”

In Kenya, patients with TB receive free treatment. A study estimates that treating drug-susceptible TB costs the government up to $160 (about KShs. 20,480) per patient. The first-line drugs mainly used include isoniazid and rifampicin.

While TB Champions fill crucial gaps, Kenya’s broader fight against TB is anchored in the National Strategic Plan for TB, Leprosy, and Lung Health (2023–2028). The plan aims to strengthen diagnostics by expanding GeneXpert testing, a modern machine that quickly detects TB bacteria and drug resistance in a few hours. These machines are spread across the country, including county and sub-county hospitals, making testing faster and more accessible.

The strategy also aims to scale up active case-finding in high-risk groups such as men aged 25–44, people living with HIV, residents of informal urban settlements, and prisoners. Preventive therapy is being simplified through shorter regimens like 3HP, a once-weekly pill combination taken for three months instead of the older six- to nine-month courses. For patients with drug-resistant TB, Kenya has moved to all-oral treatment regimens, replacing the painful daily injections that were once common.

Oral TB treatment in Kenya involves taking a combination of anti-TB drugs, which are often combined into a single pill (FDC) for standard drug-susceptible TB or as a newer all-oral regimen (like BPaLM) for drug-resistant TB. The new all-oral regimens are shorter and cause fewer side effects, replacing older treatments that involved injections. Treatment is free at public health facilities, but adherence is crucial, and programs are improving access to these newer, oral treatments for MDR-TB.

“The WHO’s End TB Strategy recognizes communities as key actors in ending TB. Kenya’s champions embody that recognition: They bring people from the shadows into care. And with the freezing of critical donor funding for TB services, maximizing local solutions like TB Champions is crucial,” said Evaline Kibuchi, National Coordinator of the Stop TB Partnership in Kenya.

The Cost of Survival

Two months after Asande’s intervention, Juma has added more than 18 pounds, but recovery comes with a price. TB has taken a toll. He cannot send money home to his aging parents. His nutrition cost swallows his earnings. But he is alive, returned to work, and clings to his daily pills like lifelines.

“Meeting Juma was timely and maybe God’s plan,” Asande reflects. “He came for SHIF registration but ended up getting the real help he would have missed.

Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. (

Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. ( Syndigate.info

Syndigate.info ).

).

Post a Comment for "TB: How Champions are Advancing Detection and Treatment in Kenya"